Room

As a fledgling college in the 1820s, Bowdoin struggled to provide adequate housing for its students, a situation exacerbated by the founding of the Medical School of Maine in 1820 and the expanding of class sizes. The Class of 1825 was the largest Bowdoin admitted to date, with 37 graduates and 8 non-graduates.

When the Class commenced its studies in October 1821, there was only space for about a third of the students at Maine Hall, the College’s only residential building. Most students lived in various rooming houses scattered along Park Row or opted to study remotely, remaining with their families in their hometown and working under a local tutor. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for example, stayed in Portland for his first year, relying on his new friend and classmate George Washington Pierce (who he met during a campus visit in May 1821) to relay both official and unofficial college happenings.

To address the housing situation, the Governing Board approved the building of “North College,” what would become Winthrop Hall, in spring 1822, to house additional students. Yet, before construction could even begin, disaster struck when Maine Hall burned. It was reconstructed within six months and Winthrop opened in Fall 1823, at last providing housing for all students who desired it.

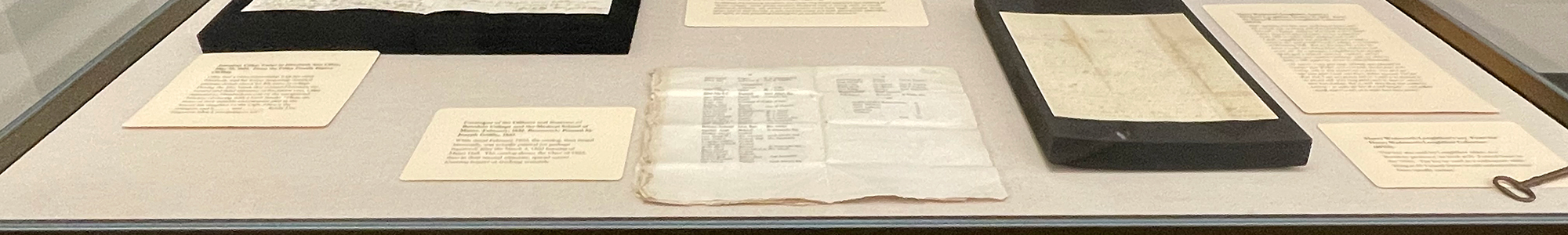

Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Bowdoin College and the Medical School of Maine, February, 1822. Brunswick: Printed by Joseph Griffin, 1822.

While dated February 1822, the catalog, then issued biannually, was actually printed (or perhaps reprinted) after the March 4, 1822 burning of Maine Hall. The catalog shows the Class of 1825, then in their second trimester, spread across rooming houses or studying remotely.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Letter to Elizabeth Longfellow, October 12, 1823. From the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collection (M112).

After spending his first year studying at home and his second year rooming with Reverend Benjamin Titcomb, a Baptist minister who lived at 63 Federal Street (where Harriet Beecher Stowe would live from 1850 to 1852, while writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Longfellow was initially excited to land a room in the newly built North College, now known as Winthrop Hall. But by the time he wrote his sister a week into living there, the jubilation had worn off. As a teenager, Longfellow had already developed a refined taste for comfort, and he found his new quarters lacking. Still, he tried to keep a stiff upper lip about it, telling Elizabeth,

“the room is a very good room, although more pleasant for Summer than Winter, as it is in back, not the front of the College, and on that account not so warm. You must not infer from what I have said that I dislike my room. No! far from that! I am very pleased with it. I wish to be disposed to be pleased with every thing which must be mine or which I must have dealings, that is, with every thing that cannot be bettered – to make the best of a bad bargain, – and content myself, that it is not, as it might have been, worse.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Key. From the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collection (M112).

This key was used by Longfellow when, as a Bowdoin professor, he lived at 25 Federal Street in the 1830s. The key he used as a sophomore while living at 63 Federal Street would undoubtedly have been visually similar.

Jonathan Cilley, Letter to Elizabeth Ann Cilley, May 25, 1824. From the Cilley Family Papers (M354).

Cilley had a close relationship with his sister Elizabeth, and his letters frequently revealed intimate details about his life away at college. During the May break that occurred between the second and third trimester of his Junior year, Cilley reported to Elizabeth on one of the unexpected benefits of staying with a local family: “There are three or four amiable and pleasant girls in the house; the daughter of the Capt. Eliza is the youngest and h_____ and ______. Really I’ve forgotten what I was going to say.”