Commencement and Beyond

Thirty-seven students graduated in the Class of 1825, the largest class in Bowdoin College’s then twenty-year history. Commencements drew large crowds, not just of family and friends, but from surrounding communities. The Class of 1825 contributed $300 to have musicians come from Boston to entertain the crowd.

While the students gave speeches, ate, and presumably were merry, they also took the opportunity to demonstrate their dislike of the President, William Allen; half of the class refused to attend the reception he threw in their honor. Hawthorne’s disdain was perhaps the greatest. He characterized President Allen as “a short, thick little lump of a man, with no talents, and, as I have been told, no extraordinary learning.” Whatever disrespect they held for President Allen, though, was out measured by their devotion for the faculty, Professor Parker Cleaveland first among them. Longfellow, in his poem delivered at the 50th reunion of the Class of 1825, expressed this devotion: “Oh, never from the memory of my heart, Your dear, paternal image shall depart.”

Perhaps among the most remarkable feature of the class was the way their lives were intertwined. Class members remained life-long friends and supported one another in their careers, even at personal costs.

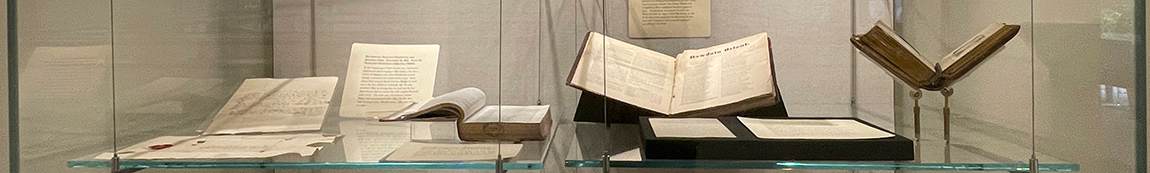

Class of 1825 Commencement Program, September 7, 1825. From the Bowdoin College Archives (A01.06).

The Class of 1825’s Commencement was a three-day affair with plenty of celebration but also a fair degree of tragedy. Gorham Deane, who was to graduate second in the class, died on August 11, 1825, three weeks prior to commencement. His place in the program was not reassigned but instead held in his honor, and he was granted his degree posthumously. Presciently, Longfellow changed the topic of his address shortly before commencement, opting to speak on “Our Native Writers,” an area in which he would soon make major contributions.

Tableware used at the dinner following the first Commencement at Bowdoin College, September 4, 1806.

From the Bowdoin College Archives (A10). In addition to the more formal aspects of Commencement, the occasion included a celebratory dinner, paid for by the members of the Class of 1825. The tableware used would have been similar, if not this set, known to be used at Bowdoin’s first commencement in 1806.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Fanshawe : A Tale. Marsh & Capen, 1828.

Hawthorne published his first novel, Fanshawe, at his own expense and anonymously. It is possible he was working on the novel while a student at Bowdoin, although it did not appear in print until three years after his graduation. The novel is set at the fictional Harley College, which most Hawthorne scholars interpret to be Bowdoin. While the book received positive reviews, it was a commercial failure and Hawthorne attempted to suppress it. He burned his copies and asked others to do the same. As a result, the book is exceedingly rare. Bowdoin’s copy of Fanshawe was donated to the College as the Library’s 500,000th volume.

Horatio Bridge’s Personal Recollections of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Harper & Brothers, 1893.

In 1893, shortly before he passed away at age 87, Commodore Horatio Bridge penned his personal recollections of his former classmate, Nathaniel Hawthorne. Bridge’s life, like so many in the Class of 1825, was profoundly shaped by his experience at Bowdoin, and particularly, by the friendships he forged here with Hawthorne as well as Franklin Pierce (Class of 1824). Not only did Bridge write Hawthorne’s biography, he encouraged his literary aspirations and subsidized some of his early publications. Hawthorne, in turn, wrote Pierce’s political biography, contributing to his election as the fourteenth U. S. president in 1853. Pierce ensured that Bridge received an appointment as the Chief of the Bureau of Provisions for the Navy, a position he held for decades.

According to Bridge’s own memories, their friendship began on a faithful stagecoach ride to Brunswick in the Summer of 1821:

Some old men will recollect the mail-stage formerly plying between Boston and Brunswick (Maine), drawn by four strong, spirited horses, and bowling along at the average speed of ten miles an hour. The exhilarating pace, the smooth roads, and the juxtaposition of the insiders tended, in a high degree, to the promotion of enjoyment and good-fellowship, which might ripen into lasting friendship. Among the passengers in one of these coaches in the summer of 1821 were Franklin Pierce, Jonathan Cilley, Alfred Mason, and Nathaniel Hawthorne--the last-named from Salem, the others from New Hampshire. Pierce had already spent his freshman year at Bowdoin College, which institution his companions were on their way to enter. This chance association was the beginning of a life-long friendship between Pierce, Cilley, and Hawthorne; and it led to Mason and Hawthorne becoming chums [roommates]….A slight acquaintance with Mason led me to call at their rooms, and there I first met Hawthorne. He interested me greatly at once, and a friendship then began which, for the forty-three years of his subsequent life, was never for a moment chilled by indifference nor clouded by doubt.”

Bet between Nathaniel Hawthorne and Jonathan Cilley. November 14, 1824. From the Nathaniel Hawthorne Collection (M085).

At the beginning of their Senior year, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Jonathan Cilley made a bet for a barrel of Madeira wine that Hawthorne would remain unmarried for twelve more years. They asked their mutual friend Horatio Bridge to hold on to the bet, which he faithfully did. He also notified Cilley in writing that he had lost the bet (Hawthorne did not marry his wife Sophia Peabody until 1842). The next year, Hawthorne visited Maine and reconnected with Cilley for the first time in many years. Months later, Cilley was killed in a duel.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Biographical Sketch of Jonathan Cilley,” in The United States Magazine and Democratic Review v. 3 (1838).

Following Cilley’s death, The Democratic Review commissioned Hawthorne to write a eulogy of his Bowdoin classmate. The copy here was owned by Bowdoin’s Athenaean Society, the literary society which included both Cilley and Hawthorne as members.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Life of Franklin Pierce. Ticknor, Reed and Fields, 1852.

When Franklin Pierce won his party’s nomination, Hawthorne volunteered to write the requisite political biography. After excusing himself as “being so little of a politician that he scarcely feels entitled to call himself a member of any party,” Hawthorne further notes that “If this little biography have any value, it is probably…as the narrative of one who knew the individual of whom he treats, at a period of life when character could be read with undoubting accuracy, and who, consequently, in judging of the movies of his subsequent conduct, has an advantage over much more competent observers, whose knowledge of the man may have commenced at a later date.” Hawthorne’s work was successful at convincing people to vote for Pierce, who won the election in a landslide. To the majority, Pierce was seen as a compromise candidate who would keep the Union together. To many in the North, he was seen as a southern sympathizer who not only kept slavery intact but allowed for its expansion. In winning the presidency, Pierce defeated another Bowdoin graduate and former classmate, John P. Hale (Bowdoin Class of 1827), who was a member of the anti-slavery Free Soil Party.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Letter to Horatio Bridge, October 13, 1852. From the Nathaniel Hawthorne Collection (M085).

Writing to Horatio Bridge shortly after the election, Hawthorne remarked “He [Pierce] certainly owes me something; for the biography has cost me hundreds of friends here at the North, who had a purer regard for me than Frank Pierce or any other politician ever gained, and who drop off from me like autumn leaves, in consequence of what I say on the slavery question. But they were my real sentiments, and I do not now regret that they are on record.” Hawthorne was referring to his discussion in Chapter 6 of Pierce’s position on slavery, which he shared: that is, while the institution was evil, the need to preserve the Union outweighed any moral or other obligation to push for slavery’s end; rather, Hawthorne asserted that over time slavery would simply run its course and die away. Pierce did reward Hawthorne for his “troubles.” He received the lucrative appointment as Consul of Liverpool, a position that allowed Hawthorne to collect fees on all American shipments going in and out of the city.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamus,” Bowdoin Orient v. 5, no. 6 (July 14, 1875).

Eleven of the fourteen surviving members of the Class of 1825 gathered for their 50th reunion at Bowdoin in July 1875. While many of the men present had distinguished themselves in their fields, none was more famous than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, then considered America’s greatest poet. His presence on campus created a stir. When he took the stage to read this poem, an ode to his alma mater prepared for the event, he was met with “vehement and continued applause” according to The Orient.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Letter to David Shepley, August 9, 1875. From the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collection (M112). Together with Photograph Album of the Class of 1825, ca. 1875. From the Bowdoin College Archives (A01.06).

Following the reunion, the surviving members of the Class of 1825 took some pains to exchange images of one another. A volume from the Bowdoin College Archives labeled “Bowdoin 1825-1875) preserves likenesses of thirteen of the surviving members of the class. In his note to David Shepley, also of the class and an attendee at the reunion, Longfellow notes: “How I wish we had photographs of all the class, as we were when we left college, instead of those melancholy silhouettes.”