Paying for Bowdoin

Despite fees that seem impossibly low to our modern sensibilities, the cost of a Bowdoin education was a challenge to many, perhaps the majority, of the students in the College’s earliest classes. The Class of 1825 was no exception. Many students worked as schoolmasters, running small one-room schoolhouses during academic breaks, to help cover their fees. Families, sometimes extended ones, pitched in as the case with Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose uncle paid for his expenses. Some students were fortunate to receive grants from charitable organizations, including Bowdoin’s own Benevolent Society.

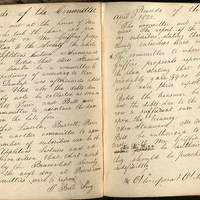

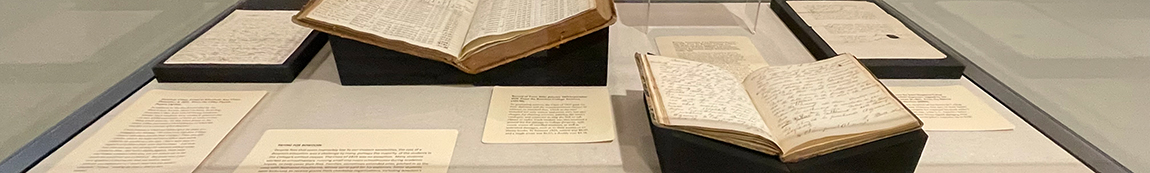

Records, Committee of the Benevolent Society, 1816-1827. From the Bowdoin College Archives (A04.08.02) and Jesse Appleton’s Lectures, delivered at Bowdoin College, and occasional sermons. Brunswick, Maine: Printed by Joseph Griffin, 1822.

The Benevolent Society was formed in 1814 by twenty-nine members who met in the chapel and adopted a constitution for the purpose of assisting “indigent young men of promising talents and of good moral character in procuring an education at this college.” The society was composed of students, notable members of the Brunswick community, and faculty members. A committee of the society, including members of the junior and senior classes, made awards to deserving students with the consent of the Executive Government of the College. Among the group’s major fundraising activities in the early 1820s was a considerable effort to distribute and sell remainder copies of sermons by the deceased Bowdoin College President Rev. Jesse Appleton to raise scholarship funds.

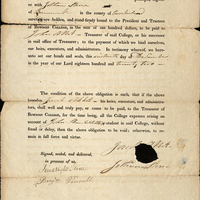

Promissory note for John Stephens Cabot Abbott’s Bowdoin expenses, signed by his father, December 16, 1822. From the Abbott Memorial Collection (M001).

Presumably each member of the Bowdoin College class had to show evidence that they or their family would be responsible for expenses incurred while a student. In this case, John S. C. Abbott’s father along with Jotham Stone signed pledging their agreement to cover John’s expenses up to $100.

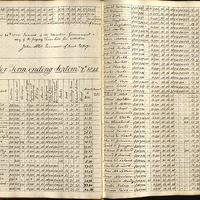

Record of Term Bills, January 1803-September 1829. From the Bowdoin College Archives (A01.08).

As graduating seniors, the Class of 1825 paid for their diplomas and the commencement dinner, in addition to standard fees, which at the time included not only tuition and room rent, but also charges for cleaning services, printing the term’s catalogue, and someone to ring the bell to call classes to order. Each student was also assessed a general fee for damage to college property, split evenly across all enrolled students, as well as individual damages, such as to their rooms or to library books. In Summer 1825, tuition was $8.00 and a single room was $6.67; a double cost $3.34.

Jonathan Cilley, Letter to Elizabeth Ann Cilley, December 8, 1823. From the Cilley Family Papers (M354).

In addition to the funds provided by the Benevolent Society, many students, including Jonathan Cilley, kept school during academic breaks. Such students were routinely granted one or two additional weeks of leave in order to run these small schools. In this letter home to his sister, Cilley provides a vivid glimpse of what life was like for a country schoolmaster:

I have procured a school and entered upon the duties of a pedagogue this morning. The school is in Topsham Village, about a mile and a quarter from Coll[ege]. There were fifty scholars came to me today and ten or fifteen more will be added to the number in a few days. And a more noisy or rogueish set of little urchins never had existence. I let them have their own way this morning for sometime without saying a word to them. And such a higgley-piggledy, hurly-burly and harum-scarum as there was, you nor nobody else in the world but myself ever saw or heard of. But pretty soon I put on a dignified s[c]hool master look and with as much authority and importance as I could crowd into one world I demanded “Silence,” nodding my head a little as was natural.